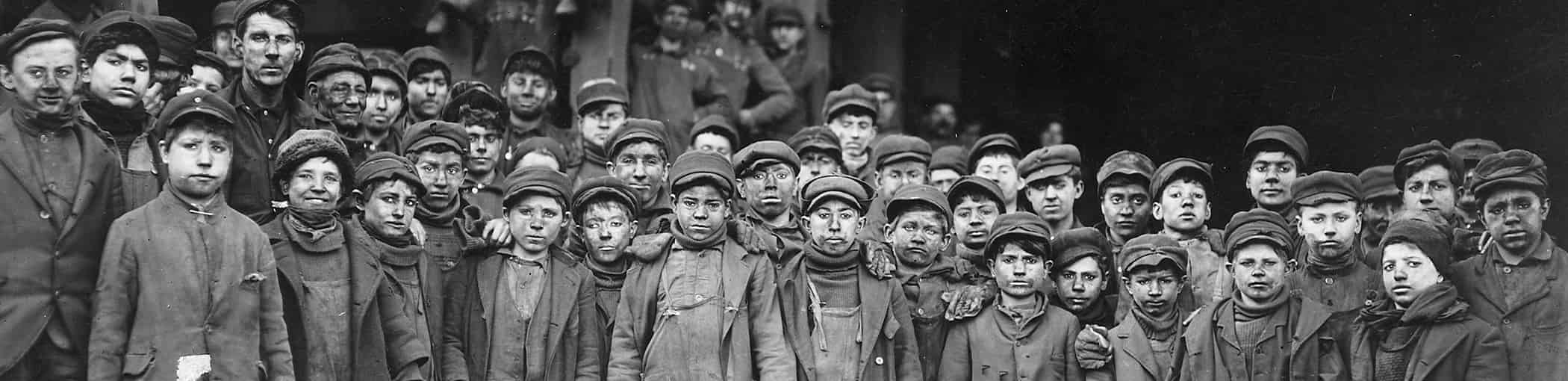

Child Labor Stories as they Exist Now Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The compelling article from The Arab News included the child labor story of 14-year-old Omar:

Omar’s heart sinks when he trudges past his closed school gates in the Jordanian capital Amman — now part of his trip to work to repair and clean kerosene heaters.

The 14-year-old, who dreams of becoming a pilot, is one of many minors experts say have been forced prematurely into the labor market.

Schools throughout Jordan have been closed for nearly a year now, and the economic fallout from the novel coronavirus pandemic has eaten into breadwinners’ ability to feed their families.

“As school is shut, I help my family financially,” said Omar, sporting a sweater and dirty jeans as he cleaned a heater with his blackened hands.

He works exhausting 12-hour days at the workshop and collapses into bed after a shower and a quick evening meal.

He earns three dinars (around $4.25) a day, which helps pay the family’s monthly rent of 130 dinars.

UNICEF anticipates that the COVID-19 pandemic will push millions of children back into the workforce. As the virus infects breadwinners in low- and middle-income countries, children who are already unable to attend school are going into the mines, mills, factories and farms to find a way to help feed their families.[1]

By the same token, the global pandemic has disrupted supply and demand from one end of the supply chain to the other. Diminished demand drives job losses for adults. Their children may have to work to contribute to the family’s survival.

The need for a substantially greater supply of other products requires additional workers. Many of those jobs may be filled by already-out-of-school children.[2]

Japan Today recently claimed that “Children who were already working before the pandemic may now be facing longer hours and worse conditions, while others could be forced to work by families struggling to survive the economic downturn.”[3]

School attendance has been canceled in Bolivia. As a result, 6-year-old Mariana Geovana and her four brothers and sisters work alongside their parents in a small carpentry shop outside of La Paz.

Andrés Gomez is 11 years old. School classes have been suspended in the Chiapas state of Mexico, where he lives. His hands that once held a pencil now wield a hammer in an amber mine.

Florence Mumbua didn’t have the capability to offer her children online classes when schools shuttered in Nairobi. Her three children, aged 12 and under, crush rock to earn about $0.65 a day. “I have to work with them because they need to eat, and yet I make little money,” Mumbua told the Associated Press. “When we work as a team, we can make enough money for our lunch, breakfast, and dinner.”[4]

Learn more about child labor then and now[1] Buechner, Maryanne. UNICEF. COVID-19 and Child Labor: A Time of Crisis, a Time to Act. https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/covid-19-and-child-labor-time-crisis-time-act/37741. October 19, 2020.

[2] Human Rights Watch. EU Parliament Vote Critical to Hold Companies to Account. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/21/eu-parliament-vote-critical-hold-companies-account. January 21,2021.

[3] Guilbert. Kieran. Japan Today. How can the world boost efforts to end child labor in 2021? https://japantoday.com/category/features/opinions/expert-views-how-can-the-world-boost-efforts-to-end-child-labour-in-2021. January 4, 2021.

[4] Verza, María, Valdez, Carlos & Costa, Willian. AP. Pandemic Driving Children Back to Work, Jeopardizing Gains. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-pandemics-mexico-india-united-nations-fffae94a31ba82437bb1bb92d5f12c0a. October 15, 2020.