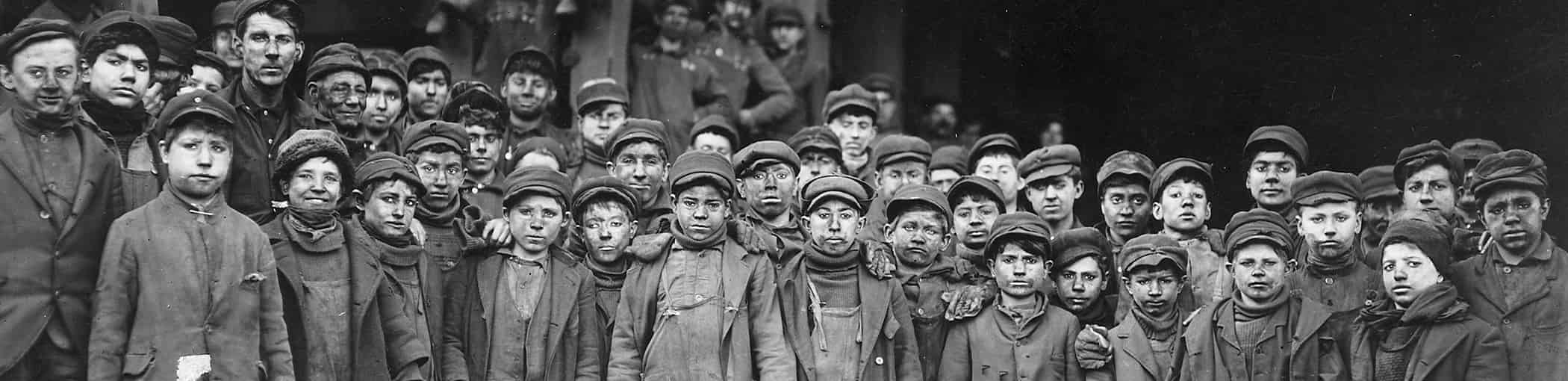

Child Labor Research – How It Existed in the Past in America

America, too, has had its share of child labor realities. In 1900, nearly 2 million children under the age of 16 where forced to work, most in mines, farms and factories,[1] according to child labor research into photos that ended child labor in the United States.

In 2021, more than 500,000 children in America are estimated to be engaged in child labor. That’s still one-quarter of the number employed a mere three generations ago.

According to the University of Iowa Labor Center,

“Forms of child labor, including indentured servitude and child slavery, have existed throughout American history.

“As industrialization moved workers from farms and home workshops into urban areas and factory work, children were often preferred because factory owners viewed them as more manageable, cheaper, and less likely to strike.”[2]

In fact, children were a major component of the American workforce from the beginning. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, children were expected to “earn their keep.”

Prior to the Civil War, “Most kids under age 15 worked up to 14 hours a day, either alongside their parents or for an employer – unless they were rich. In that case, other children worked for their families.”[3]

Throughout the entire 19th century, child labor was common in the U.S. based on the reasoning that “labor benefitted children by helping them avoid the sin of idleness” and that they provided economic empowerment by “helping to increase [production] capacity.”[4]

While it may be unpalatable to Americans, no truly effective or enforceable child labor laws existed in the U.S. until the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938[5], a full 75 years after Lincoln freed the slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Even then, the FLSA barely addressed child labor in comparison to wage and hour laws.

Numerous attempts to introduce laws prohibiting child labor prior to 1938 failed either to gain Congressional approval or, if passed, were shortly thereafter declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

For the most part, the only people concerned about eliminating child labor in the U.S. were social activists. Business owners, parents and even children themselves believed that earning their keep and learning a trade were far more important than any other option.[6] According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,

- A recruitment ad from a textile mill reasoned that it was better to send a child to work where they could earn $40 a week all year long versus sending them to school where one day they might eventually become qualified as a teacher to earn $35 a month when school was in session.

- An Italian father in Chicago remarked in grief upon the tragic death of his 12-year-old girl that “in two years she could have supported me, and now I shall have to work five or six years” until his next eldest was old enough to provide him support.”

- A survey of 500 children in multiple Chicago factories found [they] had numerous reasons why they preferred to work in the factory. While many concentrated on the negative aspects of school and discussed their dislike of learning, others highlighted the positive aspect of employment. Some children referenced the fact they could get paid in the factory. One child expressed that the employer “gives your mother your pay envelope,” while another mentioned, “You can buy shoes for the baby.”

Despite the passage of the FLSA, children reentered the labor force during World War II, with nearly 3 million actively employed in 1944, just six years after the act had passed into law. There are senior citizens alive today who labored as children up to as late as 1967 when standards were established to limit the kinds of work children under the age of 16 may perform.

Ultimately, the introduction of mandatory education laws did more to reduce incidents of child labor. Truancy officers ensured that children attended classes as required.

If Americans are to rightly understand child labor and why it exists, there must first be an understanding of the issue as it has existed – and still does – in the United States. It’s important to not forget how long our nation struggled with the issue during the years preceding our emergence as a global economic power. The predominant presence of child labor today is largely limited to nations that are attempting to advance from subsistence to economic prosperity.

Learn more about child labor then and now[1] Photography Talk. Photos that Ended Child Labor in the U.S.. https://www.photographytalk.com/photos-that-ended-child-labor. Accessed February 2021.

[2] The University of Iowa Labor Center. Child Labor in U.S. History. https://laborcenter.uiowa.edu/special-projects/child-labor-public-education-project/about-child-labor/child-labor-us-history. Accessed January 2021.

[3] Photography Talk. Photos that Ended Child Labor in the U.S.. https://www.photographytalk.com/photos-that-ended-child-labor. Accessed February 2021.

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Standards. History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. February 1, 2017.

[5] Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working.” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2017.1. January 2017.

[6] Ibid.